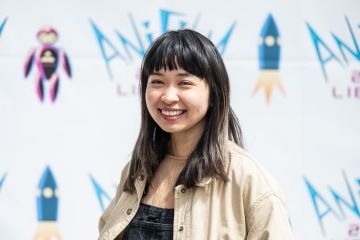

Interview: Diana Cam Van Nguyen

10. 5. 2025

Diana Cam Van Nguyen is a Czech director whose animated work ranks among the very best of what the Czech film industry currently has to offer. It’s no coincidence that her short films have appeared at some of the world’s most prestigious festivals – in Rotterdam (Apart, 2018), Locarno, or Toronto (Love, Dad, 2021). Known for her authentic, technically innovative animated documentaries, in which she often draws on her personal experience, she will be joining the jury of the Short and Student Film Competition at this year’s Anifilm. In the following interview, she talks about why young Czech animation is on the rise and how came up with the concept for her first feature-length fiction film.

In recent years, there has been talk of a new wave of Czech animation, of which you're considered a member. What’s your opinion on this, and do you agree that Czech animation is once again at the forefront of domestic film production? What do you think caused it?

Diana: I’m not sure about calling it a “new wave”, but I do see a rise in Czech animation, because it’s definitely not just a few individuals doing great work. Excellent Czech animated films have been coming out almost every year recently, and compared to live-action films, their successes at international festivals (including A-list ones) are really noticeable. What I enjoy most is the diversity of these films. Each one features a different technology, belongs to a different genre, has a different subject matter. And even though my colleagues and I influence each other to a certain extent, we also each have our own style. I don’t know what has caused this upswing, but perhaps it’s because we’ve recently become more attuned to current global trends – and not just in terms of technology.

So which colleagues inspire you the most?

Diana: Even when I first started at FAMU, I was already following the work of Jakub Kouřil and Jan Saska, and I found it incredible how far one could go with short films. That was still before the rise of Czech animation that we’ve talked about. At the moment, I consider Dávid Štumpf an exceptional talent, which has been clearly reflected in his international successes, such as winning an Emmy for Outstanding Animation for his work on the Ms. Marvel series. Even though he doesn’t often work in creative positions like directing now, it’s clear that he has incredible animation skills, and I feel very lucky to have had the chance to work with him. Of course, I’m also in contact with Daria Kashcheeva. I appreciate being able to share both the positive and negative experiences with developing a feature film with her, as well as the practical issues associated with fair compensation, which I see as very important. If I were to mention someone from the field of live-action cinema, I’d say I have a similar relationship with Vojta Strakatý and Michal Blaško.

Thanks to your films The Little One, Apart, and Love, Dad, you’ve visited many festivals and met a number of foreign animators and filmmakers. What was the most interesting part of this experience and what surprised you the most – whether in a positive or negative way?

Diana: I think I’d divide my experience between A-list festivals, which changed my life, and all the others. Participating in A-list festivals opens up a lot of opportunities and makes it easier to get into residency programmes like, for example, Cannes Residence. A turning point for me was when my film Apart was accepted to the film festival in Rotterdam thanks to a juror at the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival, where it had its premiere. At that time, I had no idea what an A-list festival even was, nor did I have any ambition to get into one. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, especially because you realize that your film is being presented alongside the works of great figures of world cinema. I felt something similar with Love, Dad in Locarno. Since then, I’ve learned the ropes of the festival world a bit, and to some extent, it’s become more of a routine for me now. As for other festivals, I think their charm lies more in how much you can enjoy them on a personal level and how many new people you get to meet. One of my favourites is Clermont-Ferrand, where I’ve encountered perhaps the most enthusiastic audience, people who were genuinely excited about watching short films, and I also really appreciate the quality of their programming. Almost every film I saw there left an impression on me and motivated me to create new stuff.

What has changed for you over the years of working in the field, and what have you taken away from your professional experience so far?

Diana: I have learned a lot. When I started at FAMU, I knew absolutely nothing about film, I had no ambitions, and at the same time I felt like everyone was one step ahead of me. I think I was really lucky that I got to travel with my student films to festivals in person, which is how I started learning about other aspects of filmmaking, such as distribution, sales, and international co-productions – things we weren’t really taught at school. I’m also fortunate to be surrounded by great people that I can trust. My producer, Karolína Davidová, and I have sort of grown professionally together. We’ve worked together on all of my short films, and now we’re developing my feature debut. Even though some might say that at this point I could reach out to someone more ambitious or more experienced, I honestly don’t feel the need to.

Recognition at festivals, numerous awards, and inclusion in various rankings all seem like great validation for the work you’ve done, but they might also bring increased pressure or higher expectations. What’s your experience?

Diana: I used to feel some pressure, but not so much now. When Love, Dad came out and was getting a lot of attention, I would hear opinions and advice like “Diana, you need to make something new quickly, or people (and funding bodies!) will forget about you,” all the time. That stressed me out a bit, because I didn’t have another idea of my own. So I snatched a script that someone else had written. I worked on that project for about six months before I realized that I had nothing to contribute to it and that I didn’t want to invest the next five years in it. It was only after I gave myself some space to breathe that the idea for my first feature film came to me. I don’t feel that sort of pressure now. I can’t expect my feature debut to be as successful as my short films, because there’s just so much competition. I’m mainly grateful for the opportunity to work on my own feature, which is an expensive affair, and it puts a lot of responsibility on the team.

By Czech standards, Love, Dad is an unusually emancipatory film, and at the same time, it can also be interpreted as a form of self-therapy. How was it made, and how do you personally perceive the way it was received – both by the public and by those closest to you?"

Diana: The development of the film was quite slow. Originally, it wasn’t supposed to be as personal as it ended up being, even though it was based on real letters my dad wrote to me from prison. It was supposed to be more of a children’s film about a relationship between a daughter and a father who can’t be together because he’s in prison. But then we took part in a CEE Animation workshop, where there were group sessions that felt a bit like therapy. There, someone told me that I didn’t have a problem with my father being in prison, but something else. Deep down, I felt that the mentors there were right, because we even had some early footage, and it just wasn’t good. So I started rewriting the script and tried to process my unresolved issues through the letter that became the backbone of the film. Doing both of those things at once was really challenging, and it complicated the whole creative process. The first version of the letter was full of misunderstanding and anger towards my dad, but that gradually changed.

Once we had the final version of the script with storyboards, everything moved very quickly. The filming and animation took about four months – in part thanks to the lockdown, when the only place you could go was to work. Even before we had a final cut, we sent a work in progress version to Locarno, where the film was accepted immediately. We approached the overall preparation of the project very meticulously. I don’t think we underestimated anything, including the marketing, which eventually paid off when the film was released. Successes came gradually. The film was screened at various festivals and was awarded at some of them, but what surprised me the most was that it’s actually possible to make a living for a relatively long time just with a short film.

As for my family’s reaction, my dad knew I was working on a project about him and his time in prison – or at least he knew about the first version. He had no idea about the later changes. He was actually the first person to see the finished film, partly because I wanted to be sure he was okay with me putting something so personal out into the world. He didn’t comment on the subject matter at all but rather asked practical questions about the shooting, the actors, and so on. But I had the feeling he was processing it on the inside. My mom and the rest of the family didn’t see the film until a year and a half later at a screening in a small art cinema in Vietnam. About thirty people showed up, and it was one of the most meaningful and pleasant Q&As I’ve ever had. A lot of young women from the audience told me how important and inspiring the topic was for them and for women in general. What I found quite interesting was that while the female members of my family cried and expressed sympathy, the men said nothing at all.

In your short films, you’ve often explored both the experience of Vietnamese in the Czech Republic as well as more personal or autobiographical topics. Your upcoming feature film Between Worlds, which deals with the dilemma of whether to give in to pressure and secure financial stability for one’s family through marriage, or to retain the freedom of an independent “European woman”, will be in a similar vein. Is this film also inspired by a true story? Could you share a bit about how you came up with the story and when is the film expected to be completed?

Diana: It’s a fictional film, but the overall idea came from my own experience when I got a marriage proposal at the age of twenty-two. My parents wanted me to marry a young man from Vietnam who was offering money in exchange so he could get into Europe. Although I thought about it for a while, it was clear to me how much it would change my life. While this dilemma represents the central plot of the film, the protagonist isn’t based on me, and we’re also working with other plotlines that aren’t based in reality. The main theme is more a reflection on what we, as children of immigrants, owe to our parents, who sacrificed their lives for us. There’s even a term for it – “debt of love” – which involves a sense of responsibility for our parents as well as a pervasive feeling of guilt. When I was preparing the concept, I had to do quite extensive research on immigration and cultural differences between Czechs and Vietnamese. I’m currently finishing the script, which I’ve been working on for about two years. If all goes well, we should start shooting in the summer of 2026 and have the film completed sometime in 2028. In terms of style, the film should be partly similar to Love, Dad as we will use the technique of collage again, but in a slightly different way this time, and about 70% of the film will be live-action footage.